- Typology

- Research

- Project

- Anthropogenic Landscapes XXX

- Partner

A seminar by Elena Bougleux, Arno Brandlhuber & Erle Ellis with Tobias Hönig & Natalie Jeremijenko

- Client

for Anthropocene Curriculum by Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) & Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science

- year

- 2014

- Location

- Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), Bezirk Mitte, Berlin, Deutschland

- The Age of Humankind asks for new ways to produce and disseminate knowledge. The Anthropocene Curriculum addresses that need by bringing together researchers, academics, artists, and civil actors from around the world to form a dynamic body of knowledge that is both experimental and self-reflexive. This collaborative educational project initiated by the Haus der Kulturen der Welt and the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science goes beyond disciplinary boundaries and established educational formats to better describe, understand, and thus meet the challenges of the twenty-first century. Anthropogenic Landscapes is 1 of 9 seminars of the 2014 campus.

- participants

- Navjot Altaf Mohamedi, Ally Bishop, Jeremy Bolen, Guido Caniglia, Zachary Caple, Benjamin Casper, Enrico Costanzo, Søren Dahlgaard, Seth Denizen, Jonathan F. Donges, Maialen Galarraga, Paz Guevara, Michael Jakob, Maya Kóvskaya, Jonas Loh, Chip Lord, Mahrizal Mahrizal, Ben Mendelsohn, Enrico Giustiniano Micheli, John Moran, Marta Niepytalska, Eric Paglia, Sascha Pohflepp, Christopher Reznich, Marc Schleunitz, Annegret Schmidt, Isabell Schrickel, Emily Eliza Scott, Francesco Sebregondi, Emanuele Serrelli, Jörg Sieweke, Hendricus Andy Simarmata, Anna-Sophie Springer, Anna Lillie Svensson, Yesenia Thibault-Picazo, Zev Trachtenberg, Marija Uzunova, Helge Wendt, Thilo Wiertz, Andrew Yang, Pinar Yoldas

XXX

XXX

Fig.___For further information visit: https://www.anthropocene-curriculum.org/

© Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW)

XXX

XXX

Fig.___Anthropogenic Landscapes

A Seminar by Elena Bougleux, Arno Brandlhuber and Erle C. Ellis with Tobias Hönig and Natalie Jeremijenko

Anthropogenic Landscapes ground us in the Anthropocene by connecting us with the land and the ecologies we shape, inhabit, and make use of, as they stress how intimately we are creating the planet that is recursively creating us. A flash fieldwork trip to the former VEB Elektrokohle (People’s Enterprise Electro-coal) in Berlin-Lichtenberg helped us to observe, study, and reshape the shift from the larger context down to the local.

Can the Anthropocene be experienced directly, in the real world, on the ground? Human transformation of the Earth is simultaneously global and local, immediate and geological, fundamentally real and absolutely abstract, intimately personal and completely collective. Within the framework of the Anthropocene, somehow, everything is connected in both human time and geological time.

The Anthropocene considers anthropogenic landscapes as outcomes of deep time processes, but also as archaeological sites, habitats to conserve for endangered species, designed spaces, up-and-coming neighborhoods, brownfields, artworks, social networks, problems to be solved—a list that continues to grow.

In this seminar, we investigated the site of the former VEB Elektrokohle (People’s Enterprise Electro-coal) in Berlin-Lichtenberg — today a highly contaminated site, mainly characterized by, among other enterprises, the “Dong Xuan Center,” a conglomerate of shops, restaurants, and places of cultural practices, mostly belonging to the numerous Berlin-based Vietnamese community. The aim of this case study was to explore the site’s meaning to both large and small scales of time and space, by connecting these with the action of local actors and local communities. People embody, and reflect in the space they inhabit, the social and economic changes occurring in the larger context. Through case-study analysis we aimed to foster the development of specific conceptual and practical tools; we aimed to experience the anthropocenic dimensions performed by the communities through the landscapes we observe on the ground, within our mind, and through our cultures.

© Anthropocene Curriculum

XXX

XXX

Fig.___Erle Ellis on Twitter

XXX

XXX

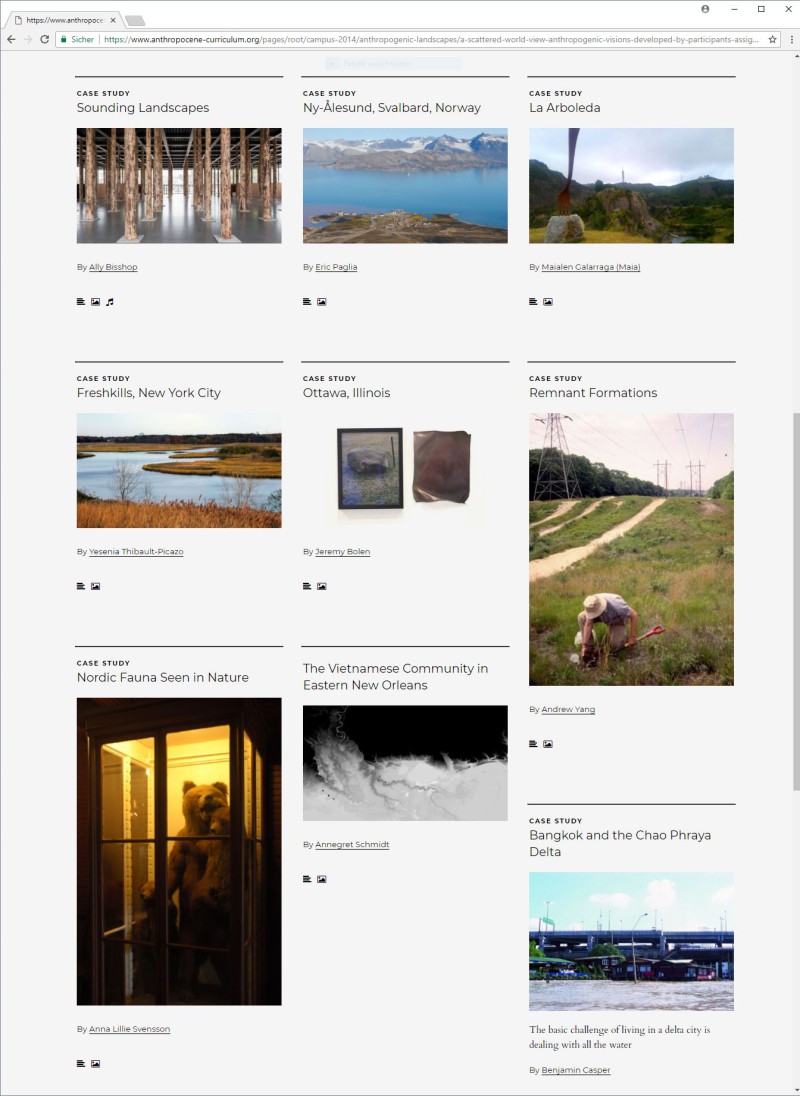

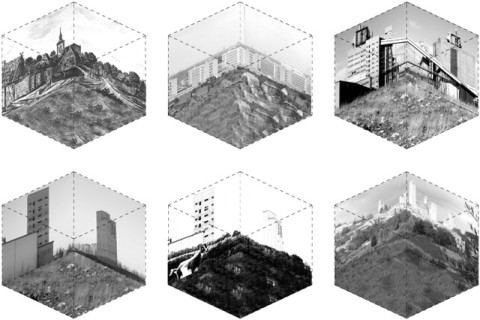

Fig.___(a) A Scattered World View: Anthropogenic Visions Developed by Participants’ Assignments

by Elena BougleuxThe task for participants was to select one meaningful example of an Anthropogenic Landscape, a case study from their personal research background, and to link it conceptually to the anthropocenic themes at stake in the Lichtenberg case study. The feedback was surprising: a rich variety of disquieting, aesthetic, accurate descriptions of unstable landscapes, relocated communities, and scattered visions of Nature, sketching an overall network of ideal relations to the Lichtenberg case in metaphorical, historical, chemical, cultural, and political ways.

The dislocated ants at the center of the Andrew Yang case study represent a powerful metaphor with which to start: a shuttle from the micro to the macro dimensionality, from the small and local to the extended and global. The ants introduce the crucial theme of change in scale in both time and space, performing invisible, tough, effective strategies of adaptation. [...]

© Anthropocene Curriculum

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(b) [...] Zooming in and slowing down to intercept the elusive rhythms of Nature, we are introduced by Ally Bisshop to the sound of a Mecklenburg human-made fir forest, which silently turned wild as the German Democratic Republic was disappearing. And pushing this slow approach to the limit, we reach the stillness of the representation of Nature set up in the Biological Museum in Stockholm, described by Anna Svensson. Anna speaks of detachment, of the material and emotional separation between the human and the natural, between the taxidermied fauna and the observers who contemplate it. The indisputable disjunction tacitly exhibited in the diorama becomes tangible evidence of radioactivity’s long-term effects described by Jeremy Bolen: risk of contamination intentionally ignored and radioactive debris guiltily spread for decades over an urban area now claim back visibility. The immanent duration of radioactive waste allows a scale-shift in the accounting of time, from the human to the geologic, forbidding the persistence in the separation between human-made causes and unintended effects, a causal disjunction that lies at the basis of most anthropocenic disasters. [...]

© Anthropocene Curriculum / Maialen Galarraga

XXX

XXX

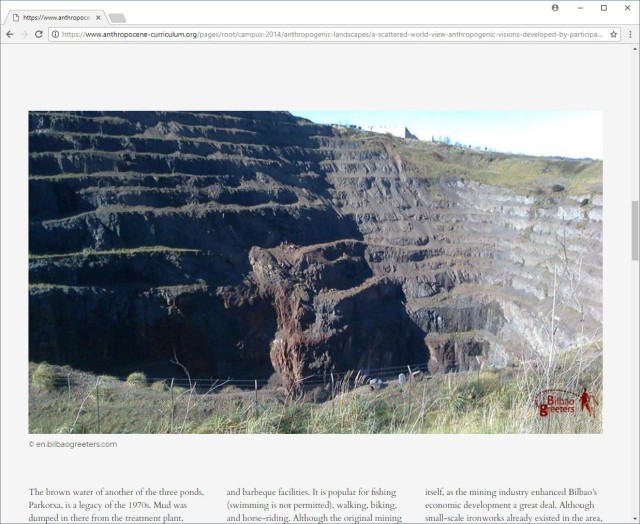

Fig.___(c) [...] Waste becomes invisible but is actually just deeply buried, accurately screened, technically processed, and aesthetically transformed until it is re-naturalized in the paramount New York landfill Yesenia Thibault-Picazo describes as an engineered kind of Nature depicted as cured environment. Self-curing environments also appear above horizons dense with coal dust in the case studies described by Maialen Galarraga and Eric Paglia. The opencast coalmine-turned leisure village in the Basque Country, with its fishing lakes, where once there were caves and tunnels, is no less disquieting than the Global Climate Observatory, set up in Ny-Ålesund on the remains of another coalmine; here, the insular small icy site is now contended by the emerging superpowers in search of a strategic location from where to observe and control the major thermal changes occurring to Arctic tides.

The landfill, the opencast mine, the Arctic observatory—these are all actors of a collective narration that tries to become accountable for the long-term transformations of the planet, in an attempt to trigger a virtuous circle of subtracting-and-restoring that eventually can reproduce a landscape, superposed with an anthropic concept of the Natural. [...]

© Anthropocene Curriculum / Eric Paglia

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(d) [...] In the work by Annegret Schmidt, we follow the migration of the South Vietnamese community on its way from the Mekong Delta to the swamplands of Eastern New Orleans, following the massive drainage intervention of the latter in the 1970s. The present landscape profile uncovers Vietnamese as well as French colonial legacies, in the small-scale agricultural styles and in the religious landmarks, insisting on a landscape highly engineered with water-management systems. In this dense scenario, we come across a flow of the Vietnamese diaspora different from the community that settled in Berlin-Lichtenberg at the same time, being guest workers of the GDR, selected from among the northern communist elites: Vietnam is sort of “recomposed” through these anthropogenic landscape visions.

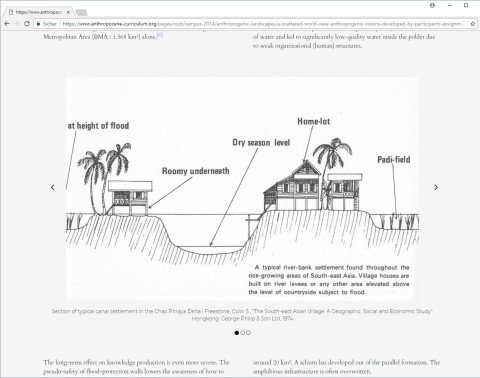

Then there is the exemplar case of resilience and co-development between social- and eco-system in the Chao Phraya Delta in Bangkok: Benjamin Casper describes the co-evolution of the community and its water-related activities, and water-dependent adaptation that has historically produced a deep socio-environmental knowledge intertwined with cultural, religious, and economic implications. The levees are changing, the waterways disappearing; the anthropic transformations of hydrologic equilibrium modify water cultures. No form of knowledge is devoid of dynamics anyway, so the co-evolution of this hydro-geo-eco-social system will continue to be a paradigmatic example.

© Anthropocene Curriculum / Benjamin Casper

XXX

XXX

Fig.___Erle Ellis on Twitter

XXX

XXX

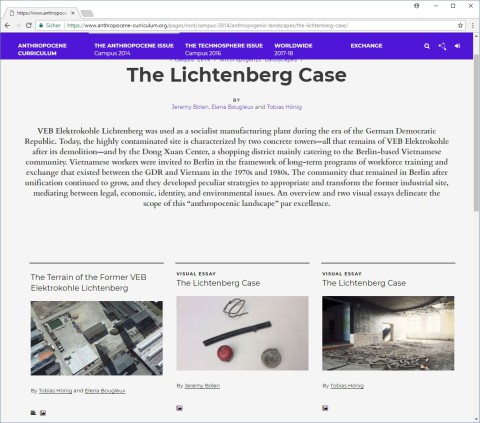

Fig.___The Lichtenberg Case

by Jeremy Bolen, Elena Bougleux and Tobias HönigVEB Elektrokohle Lichtenberg was used as a socialist manufacturing plant during the era of the German Democratic Republic. Today, the highly contaminated site is characterized by two concrete towers—all that remains of VEB Elektrokohle after its demolition—and by the Dong Xuan Center, a shopping district mainly catering to the Berlin-based Vietnamese community. Vietnamese workers were invited to Berlin in the framework of long-term programs of workforce training and exchange that existed between the GDR and Vietnam in the 1970s and 1980s. The community that remained in Berlin after unification continued to grow, and they developed peculiar strategies to appropriate and transform the former industrial site, mediating between legal, economic, identity, and environmental issues. An overview and two visual essays delineate the scope of this “anthropocenic landscape” par excellence.

© Anthropocene Curriculum

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(01)

The Terrain of the Former VEB Elektrokohle Lichtenberg

by Elena Bougleux and Tobias HönigThe site

Currently the site is divided into four distinct areas that are easy to identify on the aerial view map (Image 1): one area is still industrial and used by a factory; another is a restaurant area run by a Pakistani entrepreneur; the third and largest area on the site is the so-called “Dong Xuan Center,” a huge conglomerate of Vietnamese shops and restaurants; and finally there is a “green strip,” comprising land that seems to be considered not too contaminated and is grass-covered with a few trees. This strip divides the whole site from the surrounding area before the horizon shifts into the prefabricated slabs of GDR mass housing. [...]

© c/o now

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(02) [...] In the well-established “Dong Xuan Center,” several workshops found their home, now comprising the “largest Asian market in Berlin.” Close by, the building still owned by “Pantrac,” the company that bought the site from Treuhand after the reunification of Germany, produces carbon and graphite objects as it has done since 1997. The main VEB factory buildings were demolished, but the two giant concrete towers that remain were preserved simply because it was too expensive to dismantle them. All the steel components of the former factory, however, were sold to China. [...]

© Jens Kirstein

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(03) [...] The soil on the site is highly contaminated; therefore, the whole surface has been paved over with concrete. In some areas, the concrete seems to be unstable. Soil pollution apparently has not affected the local perception of the danger the contamination may pose, and economic activities continue to flourish. The entire area around the two concrete towers is currently owned by a Pakistani entrepreneur who established part of his business empire alongside a Tandoori restaurant on the site. Although his permit only covers the running of the restaurant, he runs it as a canteen to serve all the on-site workshops. The loose regulatory framework regarding land exploitation is due to the German political transition in the 1990s, which created the preconditions for the present lack of clarity with respect to the legal situation of the many businesses on the site. [...]

© Jens Kirstein

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(04) [...] In order to sell land parcels belonging to the site, the owner was obliged to construct a reservoir to act in accordance with fire-safety regulations. The giant pool subsequently constructed is affectionately and somewhat ironically known to locals as the “swimming pool” (see image below). Some of the soil removed for the realization of the reservoir was used to construct a small hill on which grass seed has been grown; the vision is to one day have goats grazing on it. The remaining soil became the basis of a huge platform of around 60 cm high. This giant sarcophagus, the size of a tennis court, finally furnished with a number of street lamps, may become an ice-skating rink in the future. [...]

© Jens Kirstein

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(05) [...] During several visits to the Lichtenberg site prior to the Campus 2014, we explored the definitions of places and spaces that the people working in, living in, and using the space for diverse activities currently use. Naming a spot of land is a well recognized human trait that frequently refers to people’s perception of its actuality, what it is destined to become, or the owner. In the case of the Lichtenberg site, the names people know it by indicate an element of wishful thinking, or define a would-be hypothesis that surely cannot be understood in a literal sense. In particular, considering the highly polluted, ugly, rather than inviting nature of the site’s features, the (nick)names attributed to places on it represent a project, and express an idea of development and change. People speak of a possible future for the place in clearer and shorter words than a detailed map. Both the “swimming pool” and the “ice-skating rink” refer to leisure and entertainment, although a somewhat standardized conception. The “hill” and the idea that one day goats might be left free to graze on it, as a way of nurturing it, speak to people’s desire to “go green,” a means of inscribing value into a heavily exploited area of land where clearly grass has near zero value. [...]

© Jens Kirstein

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(06) [...] The people

Berlin hosts a large community of Vietnamese people, many of whom arrived during the 1970s thanks to the workers’ exchange programs established between the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and the former GDR. The Vietnamese workers who were selected for special training programs among the local elites in East Germany did not plan to emigrate permanently to Europe, and they expected to return to Vietnam after the five-year training concluded. No project or program was dedicated to integrate the community in East Germany; almost no one learnt German, and, generally, contact with German society was confined to a minimum. [...]

© Jeremy Bolen

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(07) [...] A completely different situation can be observed with the South Vietnamese community that emigrated to West Germany. Opponents of the Vietnamese socialist regime escaped from the country without any real hope of ever returning, and special facilitating programs established to promote integration were largely successful. The detailed study of these processes goes beyond the scope of the current case study, but, in outline, the relevant data suggests that to this day the split in the Vietnamese community in Germany is apparent, reflecting the different emigration processes, reasons for emigrating, and political views—in Vietnam as well as in Berlin. [...]

© Jens Kirstein

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(08) [...] In East Berlin, the Vietnamese workers were mainly employed at VEB Elektrokohle. After the factory closed, however, only a small number accepted some financial support to return to Vietnam. The majority remained in Germany illegally, experiencing several phases of isolation and economic crisis. These factors in all likelihood resulted in their determination both to provide a livelihood and to meet all primary local needs within the same community. This large migrant community, which on the one hand has a longstanding presence in Berlin, and on the other hand lives quite separated from the rest of society, is a base for the emergence of a sort of “enclave system” with a robust economic and cultural autonomy. [...]

© Jeremy Bolen

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(09) [...] Contributions

The Anthropocene can be neither untangled nor scaled down from its complex multilayered composition. Pertinent for the Anthropocene are large- and small-scale features; an anthropogenic landscape is qualified, at the same time, by its peculiar location, its history, its ecological context, population, and geological substrates, and by the chemical composition of its soil, the altered nitrogen cycle, and the local disappearance of water. Therefore, the investigation of a landscape in the Anthropocene requires a multidimensional and multi-temporal vision, which means the simultaneous activation of dissimilar research perspectives converging to assemble a new way of perceiving. In this seminar, we tried to keep such perspectives both simultaneously activated and open to the possibility of working jointly. [...]

© Jeremy Bolen

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(10) [...] The “new knowledge needed” may emerge from the bordering, conflicting areas between well-established research disciplines; borders between disciplines, viewed as the transition of phase spaces, are discontinuous fields with an open topology, more adequately dealt with through a variety of superposed and homogeneous metrics. In this seminar, participants were seen as owners of specific metrics, both disciplinary and cultural, that needed to be part of the network and to become part of the dialogue. The Berlin landscape was our connecting ground. In our local Anthropocene ethnographic experience in the Lichtenberg district, we tried to connect local and global, past and future, community and world system. Our goal was to bring the global down to a human dimension—to experience it as a neighborhood and as a landscape—and to observe the global-geologic sedimented history of our selected landscape while simultaneously seizing the long-term consequences of short-term events and local behaviors. [...]

© Jeremy Bolen

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(11) [...] As a preparatory task, participants were asked to select an “individual case study” representing their vision of an anthropogenic landscape, showing evidence of long-term transformation enacted by social and environmental processes relevant to the Anthropocene in some way, which they were asked to document and support in terms of socio-cultural, economic, ecological, and geological evidence. [...]

© Jeremy Bolen

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(12) [...] As a second step, participants were asked to select a specific perspective to investigate and describe their own case study, a conceptual crosscut through the multiplicity of entangled meanings that constitute the anthropocenic relevance of their selected examples. We called this selected perspective a “conceptual tool,” and the aim was to use it in an attempt at a focalized understanding of the seminar’s main case study. [...]

© Jeremy Bolen

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(13) [...] Finally, the fieldwork: a short but intense external tour brought the participants to explore, experience, interview/record, and touch the reality of the former VEB Elektrokohle Lichtenberg site. Initially established in the predominantly agricultural district of Lichtenberg, just outside the city limits of Berlin, it was then taken over by the Siemens company—a synonym for Germany’s rapid growth during the Industrial Revolution. The area was used as a socialist manufacturing plant by VEB Elektrokohle during the era of the German Democratic Republic (GDR, 1949‒90). Today, the highly contaminated site is characterized by two concrete towers—all that remains of VEB Elektrokohle after its demolition—and by the Dong Xuan Center, a shopping district mainly catering to the Berlin-based Vietnamese community. Vietnamese workers were invited to Berlin in the framework of long-term programs of workforce training and exchange that existed between the GDR and Vietnam in the 1970s and 1980s. The community remaining in Berlin after unification continued to grow, and developed peculiar strategies to appropriate and transform the former industrial site, mediating between legal, economic, identity, and environmental issues. [...]

© Jeremy Bolen

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(14) [...] A theoretical driver provided by ecology to seize the relevance of the Vietnamese community in transforming the former industrial space is the “niche-construction” process. We wanted to read the Lichtenberg district in its multiplicity of anthropocenic meanings, landscape potential, and niche-construction effects. [...]

© Jeremy Bolen

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(15) [...] While anthropocenic issues in general demand large spatial and temporal perspectives, we selected a rather narrow example: our case study focused on an area in a specific district of Berlin, a relevant but not a crucial or vital case. Why select a small-scale example? Is it a productive choice? Is small-scale a synonym of an easier scale? And/or is it a synonym of a faster transformative process, somehow perceived as an easier process to grasp? [...]

© Jeremy Bolen

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(16) [...] Scales decide the meaning and the reliability of models: we asked whether the study of small-scale examples can help to construct larger pictures, and what the larger impact of an “ecological niche” like ours might be: Does Berlin as a cultural context affect and feed back the relevance of a small-scale experiment? Finally, can a small-scale example be easier to study while at the same time be highly instructive? [...]

© Jeremy Bolen

XXX

XXX

Fig.___(17) [...] In answering all of these points, the seminar was a successful challenge. Groups of randomly assembled participants explored the former VEB site in Lichtenberg, wandering through the remains of the industrial plant, the Vietnamese covered market, the Pakistani restaurants, the “swimming pool” construction site, and the hills of debris seeded with cotton. Groups pursued different observational goals: some planned according to the conceptual network of tools commonly discussed, and others assembled new gazes negotiated with the unexpected. Information was gathered by following improvised or well-trained informants we met on site, collections of multiple recordings took shape in the form of videos, photos, sound, objects, impressions, and (un)pleasant emotions.

© Jens Kirstein

XXX

XXX

Fig.___Participatory Governance

Statements by Stella Veciana (artistic researcher, Federation of German Scientists, Berlin),Tobias Hönig (architect, Berlin), Christoffer Brick (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, Berlin). Discussion moderated by Marco Armiero.

Many seem to share the opinion that for a soft landing into the Anthropocene, any response taken to the crises at hand must be legitimized through democratic procedures of power. This is, no doubt, a huge challenge, if only departing from the crisis of democracy itself: how can a concept, originally developed within the operational context of a localized city-state, be translated to scales that contain multiple geographies and subjectivities, that is, to the world? The concept of “power of, by, and for the people” not only challenges and is challenged by an extended notion of agency, it also stands in contrast to “history as usual” and the principles governing our present societies – that is, the tendency for social organization to quickly escalate into states of emergency under external pressure, as well as the inherent “dissipative tendency” of democracy to be overwritten by the technocratic constitution of expert societies.

A truly civic society resting on broad participation, commitment, interest, and active involvement is rare. Who participates and who delegates participation? What is the role of leadership? Who takes responsibility for decisions? How can we re-address notions near and dear to the ideals set forth by democratic values – participation, engagement, consensus – to take into account multilayered processes and variably distributed stakeholders? Do we need different models of governance, must we tap into other non-political orders of alliance, affinity, and relationality?

© Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW)